Uneasy lies the Head that wears a Crown!

Much of what once made Austria so great is now gone. People who enjoyed great popularity are no longer with us.

Much of what once made Austria so great is now gone. People who enjoyed great popularity are no longer with us.

A lot has been forgotten; entire places have even disappeared, sometimes having fallen victim to horror. It is curious how selectively people remember. Which people do we hold in our memories and whose countenance gets lost in the corners of our minds? How much is able to stand the test of time?

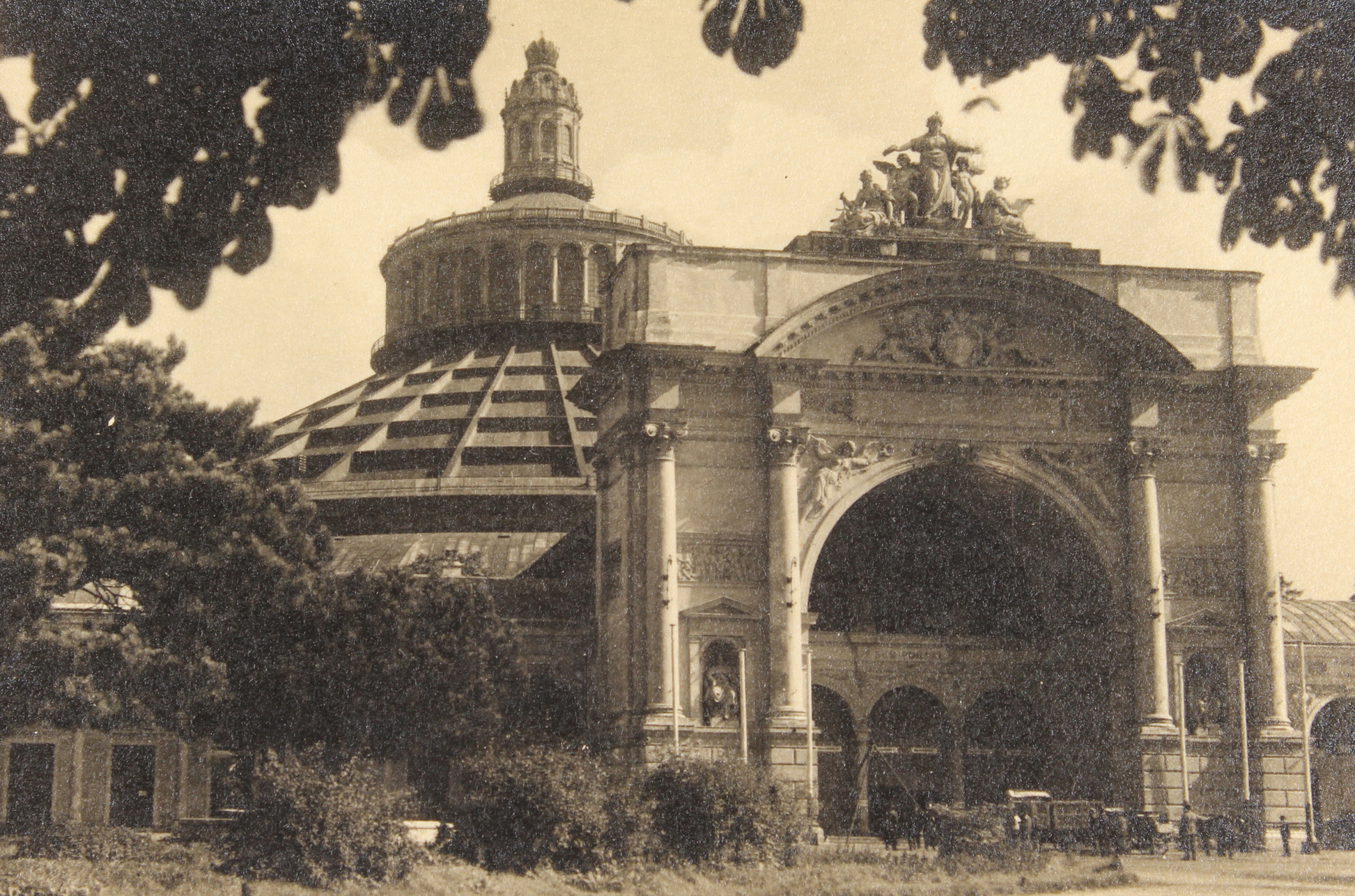

In 1937, the Rotunde disappeared from the face of the city of Vienna. This was a building that had once been among the most impressive in all the world. With a diameter of 108 metres, the Rotunde in Vienna was at the time the largest cupola in the world. The fire of September 17 engulfed a remnant and architectural masterpiece of the Danube Monarchy and one of the sites of the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair.

In 1892, the Vienna Rotunde became a silent witness to another encounter during the International Music and Theatre Exhibition (Internationale Ausstellung für Musik- und Theaterwesen) Two people met who significantly changed the world.

View of the Rotunde 1892

One of them changed the map of Europe, while the other shaped the world of music, and for a moment the two of them stood directly across from each other and the world paused for a moment, if only for the blink of an eye as far as history is concerned. Such moments are often serendipitous strokes of fate, like the one captured in this painting ...

Ludwig places his fingers gently on the keys. He wants to play his instrument. The instrument should speak for him and tell his personal story. There’s no sense in explaining music, least of all the sound he is attempting to perfect. Beads of sweat appear on his forehead, and the tight-fitting tuxedo compels him to maintain his composure. Ludwig cannot decide which piece to play, for how does one decide on the right one out of a sea of tones? Yet even before he is able to think clearly, his fingers get to work. He is neither a composer nor a pianist, although he understands the world of tones and sounds better than anyone, and he thus becomes a character in his own story, while the individual tones begin to form and a musical play of colours is released from the grand piano’s body.

1892 - Ludwig Bösendorfer plays for Emperor Franz Joseph I

His vis-à-vis smiles hardly noticeably; the smile darts but briefly over his countenance, for he must also maintain his composure.Ludwig concentrates on his playing. He wants to make the range of octaves of his creation noticeable and thus reaches into the bass register. Now it is Ludwig who smiles, for he recognizes that his creation has the desired effect.

The people present appear taken by the sound. No one utters a word. The clamour of the visitors seems to have faded, for in this moment there is only music, no politics, no regency. In this moment only the infinite universe of music exists, the one Ludwig summons on most days. He is the unrelenting pacemaker of his actions, which drives him forward in his pursuit of perfection. Once the final tone has died away, he catapults those present back to the present. Everything is silent for a split second. All eyes are now on the bearded man who laid his hand on the piano and the dedicatee of Ludwig’s playing.

When Bösendorfer began playing, Franz Joseph placed his hand on the body of the grand piano. He must maintain his composure and is glad that his tightly fitting uniform helps him to do so. The military drill was also helpful in this connection. He attempts to suppress his budding smile as well as possible. He knows the unmistakeable sound all too well, a sound he has heard so often on his own premises, just like in the Villa Schratt. It is the sound that he finds so fascinating, the neatly arranged rows of octaves. Bösendorfer knows how to produce bass tones that create a pleasant rumble in the abdominal region. Once again he suppresses a smile. He wants to close his eyes, but he needs to perform well. For a fleeting moment he is able to feel the freedom underlying the music. In this freedom he is also able to feel Bösendorfer, absorbing his spirit, his pursuit of greatness and perfection. For a fleeting moment Franz Joseph forgets who he is, a gift he greatly appreciates. Once the final tone has faded into silence, he is himself once more, again aware of the weight of regency.

The whole audience directs its gaze toward the emperor. What will be his verdict? How will he react? The emperor starts to speak, hesitates, then cannot resist: “Excellent, Bösendorfer, truly excellent!”

2018 - Todays view of the place of the former Rotunde / Photo: Roland Pohl

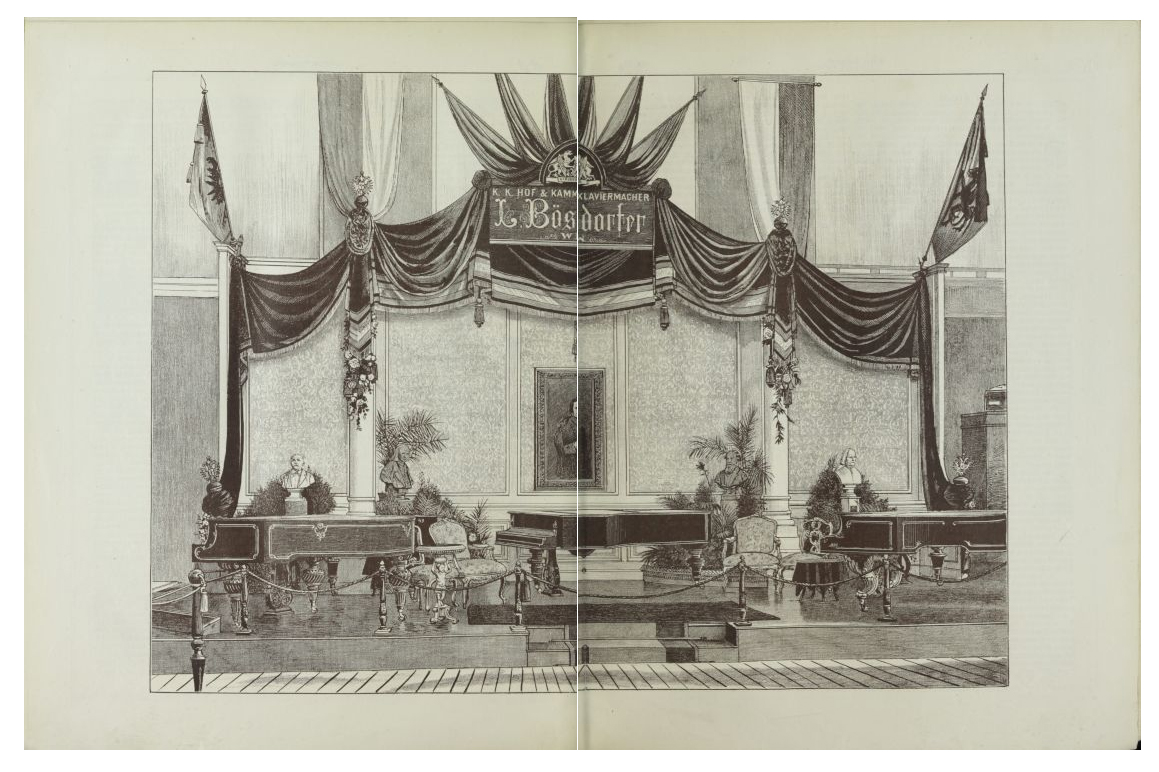

Among the most outstanding and popular details on display at the theatre and music exhibition is indisputably that of our famous piano industrialist Ludwig Bösendorfer. It would truly be carrying coals to Newcastle, as they say, if one wished to examine the significance of Bösendorfer and his establishment: The sound of this name has for years resounded victoriously throughout the world, bringing honour and glory to the Austrian, the Viennese arts industry. Nonetheless, Bösendorfer’s exposition in the Rotunde indeed deserves the most intense attention, for it offers something novel and surprising.

The Bösendorfer exhibition group already captures the viewer’s attention through the systematic harmony of the arrangement of their instruments, by presenting the transition from the smallest to the largest size—exhibiting the gigantic grand piano next to the miniature grand piano. The transition is conveyed by a magnificent baby grand [Stutzflügel] in mahogany with gold in the style of Louis Quinze. The slightly larger baby grand [Mignonflügel] is lovely, with engravings in gold and shows the so-called “Viennese construction” type. The pièce de resistance of the exhibition, however, is represented by a large concert grand piano, positioned between the baby [Stutzflügel] and miniature grands. This piano has an entirely new construction with 8 3/4 stringing and a compass of 7 3/4 octaves.

This newest creation of Bösendorfer’s outstandingly piques the interest of both piano makers and practicing artists — in a word, all the experts who unanimously describe the new instrument’s construction as the most successful ever accomplished in the history of piano making. The individual character and the characteristic advantage of the new construction lie not only in its significant amplification of the sound compared to instruments to date — an amplification through which the new concert grand should prove itself in large halls and orchestral productions (the grand piano did, in fact, prove itself when it was placed in the Rotunde several days ago, where it was tried out; even in this gigantic room it had such a powerful effect that a project was immediately initiated to have the instrument played by great artists on the piano, placed here, directly in the Rotunde) — but the singing quality and the tone colour of the new instrument are captivating in their magic.

ANNO/Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

The latest sensational creation by Ludwig Bösendorfer, which has been given the popular moniker “Bösendorfer’s gigantic grand piano,” has also earned the fullest recognition and direct, on-site interest of His Majesty the Emperor himself; His Highness distinguished Herr Bösendorfer during his visit to the exhibitor with the flattering request to play the new instrument himself. The emperor expressed himself in the most benevolent and gracious words for the new creation and extended the very best wishes to Herr Bösendorfer for this latest master achievement by his establishment.

When several days later, Her Royal Highness, the widowed Crown Princess Stéphanie visited the exhibition, Herr Bösendorfer had to play on the “gigantic grand piano” for the noble lady, who likewise spoke most appreciatively about the new instrument and asked Herr Bösendorfer whether the new gigantic grand piano would soon be used in concerts — and then expressed her vivid desire to hear Herr Alfred Grünfeld play the new instrument. Several days later, our outstanding artist hastened to oblige the Crown Princess and produced downright sensational effects on the new instrument, which were acknowledged with the warmest praise by the noble listener. The Crown Princess congratulated Herr Bösendorfer in the most benevolent way on the creation of this new instrument, on which the advantages of the new Bösendorfer system and the mastery of the piano virtuoso could reach their fullest potential.

Herr Bösendorfer thus found the most well-deserved recognition all around for his new creation. We also permit ourselves to express our most heartfelt congratulations to our famous compatriot, who has brought the Austrian arts industry the most resounding honours, on his latest creation, a creation through which the great arts industrialist has placed himself at the top of the piano industry worldwide according to the judgement of all the experts. In the vernacular, the new instrument — as previously mentioned — has been christened the “gigantic grand piano.”

The “gigantic grand piano” may not increase the popularity of Ludwig Bösendorfer — for the name can no longer become any more popular than it has already been for years — although carried by this popularity, it will bring his resounding fame throughout the world. Apropos the popularity which Ludwig Bösendorfer enjoys in Vienna and amongst the Viennese, it must be remarked that besides being the great arts industrialist, Bösendorfer’s personality plays no small part in this popularity. The humility, simplicity and amiableness of this outstanding person have won him nearly as many friends as his mastery in the piano industry has won him admirers.

One further circumstance has also contributed no little to popularising the name and personality of Ludwig Bösendorfer — his passionate love of riding and racing sports. Bösendorfer is the Viennese sports enthusiast par excellence—in any and all weather he can be found at the racetrack, among whose typical appearances the slender man with the grey-white head, the good-natured, sarcastic smile on his lips, the inevitable yellow overcoat and the inevitable Homburg hat belong. And who knows Bösendorfer not as a confident four-hand-racer — the considerably tough accident that occurred some time ago and landed him on a hospital bed could not spoil his enthusiasm for sports and driving, his “one and only passion” — he still rode “dashingly and confidently” down the Hauptallee, our dear Ludwig Bösendorfer, the master of piano making and reins, an Austrian, a Viennese the likes of which cannot easily be found, and of whom all Austrians and Viennese may justifiably be proud.”